You are here

As someone who was trained originally as a psychologist but who found a philosophical home in psychiatric rehabilitation, I have always been impressed with the degree of openness that our field has shown to the input of folks whom it serves, i.e., people with mental health and addiction challenges. By explicitly acknowledging the value of lived experience, psych rehab has made it possible for people in recovery to play an ever-increasing role in shaping how services should be conceived, delivered and evaluated. This has brought many peers into the field as practitioners and leaders, and I believe that the resulting benefits and enrichment go in multiple directions.

What I’d like to do in the space which follows is identify what I see as some interesting overlap between the discipline of psychiatric rehabilitation and that of peer support. I offer this observation having been closely aligned with both fields over the past several decades.

In the mid-1980’s I worked at a state-wide program (the NJ Self-Help Clearinghouse, which is still in operation) which maintained state and national listings of self-help groups for a wide range of problems, and which helped people—both lay and professional--start these mutual support groups if they were so inclined. It was in that context that I became involved in what at the time was being referred to as the mental health consumer movement, also known as the psychiatric survivor- and sometimes the C/S/X (consumer/survivor/ex-patient) movement. “Consumer-providers” and “prosumers” were two terms which people used at the time to identify themselves as people with lived experience with mental illnesses who were helping others deal with the same--in today’s parlance, peer supporters. In the addiction field, similar work was being done (and had been for a while), and if you were someone “in recovery” it generally meant that you were “clean and sober” and using your experience to help others achieve a similar state.

For a variety of reasons, I remained very interested and involved as a community psychologist in the continuing emergence of peer support as both a field and a discipline, and very early in its development, I had the opportunity to become connected with the newly forming National Association of Peer Specialists (NAPS, later to be re-named iNAPS). Steve Harrington, its founder, recognized that there were roles to be played by non-peer allies, and I was fortunately in the right place at the right time to become one of those allies. I believe that I was also well served by following a dictum which I first heard from Self-Help Clearinghouse founder and recently-retired Director, Ed Madara, which suggests that when working with “self-helpers,” professionals should be “on tap, not on top.” These are wise words, and I believe that they hue rather closely to several of psych rehab’s core principles.

iNAPS has played a critical role in the evolving definition of peer support, and in 2012 convened a task force at its 6th Annual Conference which would eventually obtain feedback from over 1000 peers throughout the US in a joint effort with SAMHSA to identify the core values of peer support and what those values would look like in practice. The National Practice Guidelines for Peer Supporters was issued in the summer of 2013 as both a consensus and guidance document for those who are providing or supervising peer support services. Many different codes of ethics and practice standards were considered by the initial task force; ultimately--and impressively--there was 98% national agreement on the following descriptors of what peer support is, and what peer supporters do, in practice:

Peer Support is: | And therefore, in practice, peer supporters: |

1 Voluntary | Support choice |

2 Hopeful | Share hope |

3 Open-minded | Withhold judgement about others |

4 Empathic | Listen with emotional sensitivity |

5 Respectful | Are curious and embrace diversity |

6 Facilitative of change | Educate and advocate |

7 Honest and direct | Address difficult issues with caring and compassion |

8 Mutual and reciprocal | Encourage peers to give and receive |

9 Equally shared power | Embody equality |

10 Strengths focused | See what’s strong, not what’s wrong |

11 Transparent | Set clear expectations and use plain language |

12 Person driven | Focus on the person, not the problems |

Now let’s compare this with the twelve core principles and values of psychiatric rehabilitation, as identified on PRA’s website. I’ve underlined words and phrases which I believe are the essence of each:

Principle 1: Psychiatric rehabilitation practitioners convey hope and respect, and believe that all individuals have the capacity for learning and growth.

Principle 2: Psychiatric rehabilitation practitioners recognize that culture is central to recovery, and strive to ensure that all services are culturally relevant to individuals receiving services.

Principle 3: Psychiatric rehabilitation practitioners engage in the processes of informed and shared decision-making and facilitate partnerships with other persons identified by the individual receiving services.

Principle 4: Psychiatric rehabilitation practices build on the strengths and capabilities of individuals.

Principle 5: Psychiatric rehabilitation practices are person-centered; they are designed to address the unique needs of individuals, consistent with their values, hopes and aspirations.

Principle 6: Psychiatric rehabilitation practices support full integration of people in recovery into their communities where they can exercise their rights of citizenship, as well as to accept the responsibilities and explore the opportunities that come with being a member of a community and a larger society.

Principle 7: Psychiatric rehabilitation practices promote self-determination and empowerment. All individuals have the right to make their own decisions, including decisions about the types of services and supports they receive.

Principle 8: Psychiatric rehabilitation practices facilitate the development of personal support networks by utilizing natural supports within communities, peer support initiatives, and self- and mutual-help groups.

Principle 9: Psychiatric rehabilitation practices strive to help individuals improve the quality of all aspects of their lives; including social, occupational, educational, residential, intellectual, spiritual and financial.

Principle 10: Psychiatric rehabilitation practices promote health and wellness, encouraging individuals to develop and use individualized wellness plans.

Principle 11: Psychiatric rehabilitation services emphasize evidence-based, promising, and emerging best practices that produce outcomes congruent with personal recovery. Programs include structured program evaluation and quality improvement mechanisms that actively involve persons receiving services.

Principle 12: Psychiatric rehabilitation services must be readily accessible to all individuals whenever they need them. These services also should be well coordinated and integrated with other psychiatric, medical, and holistic treatments and practices.

So, to summarize with just the underlined words and phrases, the twelve core principles of psychiatric rehabilitation include:

1. Hope and respect

Learning and growth

2. Culture is central

3. Informed and shared decision making

4. Build on strengths and capabilities

5. Person centered

6. Community integrated

7. Self-determination and empowerment

8. Natural supports

9. Multi-dimensional

10. Promote health and wellness

11. Emphasize evidence-based, promising, and emerging best practices

12. Accessible, coordinated, integrated

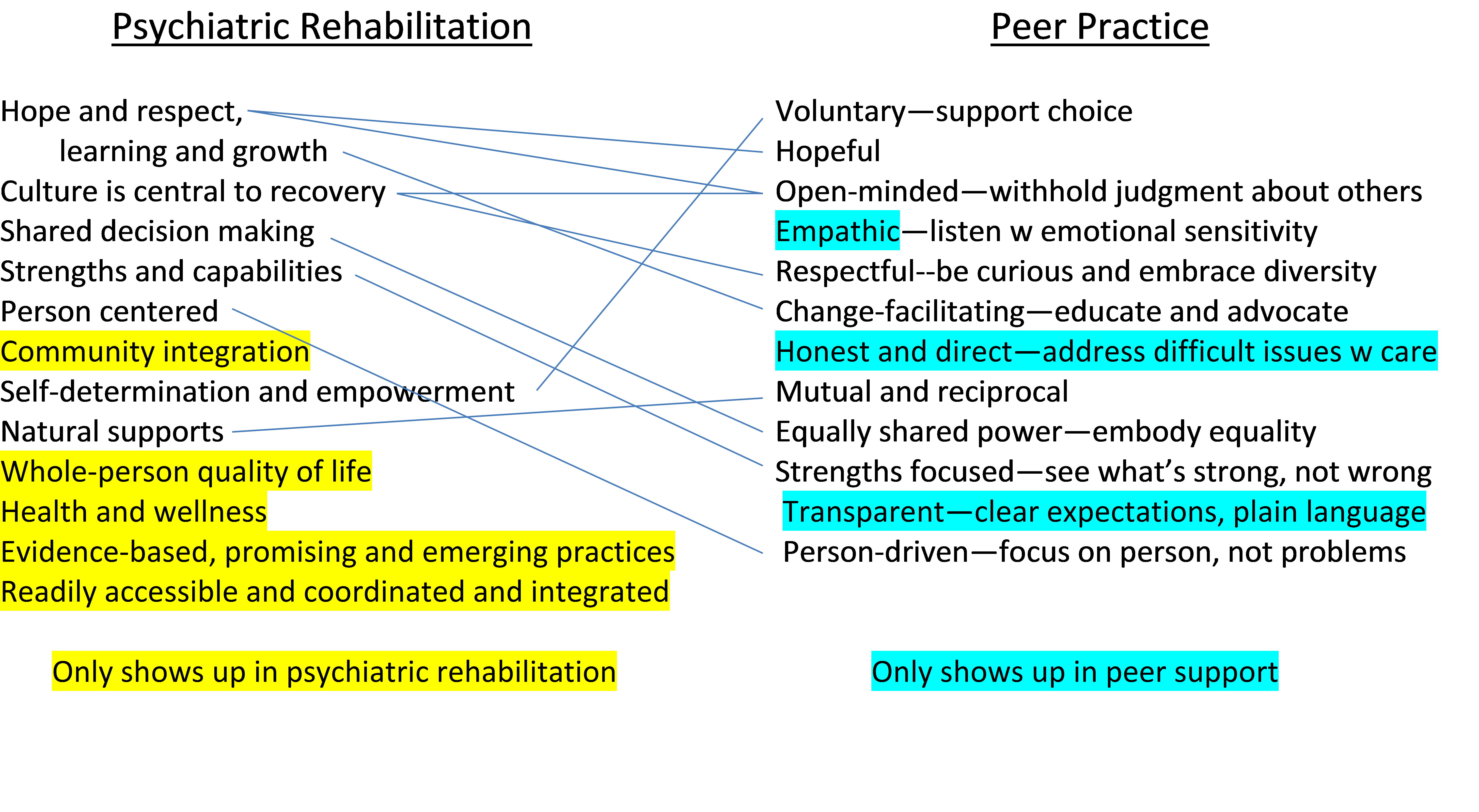

By now it should be clear that there is significant compatibility and even overlap between the core principles of psychiatric rehabilitation and the practice guidelines of peer support. The following table is a cross-mapping of the two:

I see this as a partial explanation of the affinity between the two fields. Moreover, as someone who practices in one and sees the other enacted on a daily basis, I believe that the items which only appear on one side of the table or the other are concepts which members of neither discipline would eschew, and in fact often embrace. After all, what psychiatric rehabilitation practitioner would reject the ideas of listening w emotional sensitivity, addressing difficult issues with care, or using plain language to convey clear expectations of someone with whom s/he is working? And similarly, while peer supporters generally take their priorities and goals directly from the people with whom they are working, community integration, health and wellness, and multi-dimensional, whole-person work are probably somewhere in their mindsets, at least as far as those ideas have been part of what enabled them to reach the place in their own recovery where they are now helping others.